Some journeys begin with a checklist and a plan, mine began with a ferry, a pounding heart, and a silent prayer. I didn’t know fear until I found myself standing on a shaky pantoo (ferry), crossing the river from Kpando into Krachi in Ghana’s Oti Region. Beneath me, the water looked like it could swallow me, above me, the sun was doing the absolute most, and around me, everything was foreign, language, landscape, expectations. And within me? Panic. I was en route to supervise endline data collection for a project I had recently joined, and now, I was coordinating its entire evaluation. Three months in. It was both an opportunity and a serious responsibility. This was my first time leading an evaluation of this scale. Although I hadn’t been part of the project from inception, I was given the necessary support and entrusted with guiding the evaluation process for the AI Teachers Project, funded by the Daara Innovation Fund. The project, implemented by Lead for Ghana and Shule Direct in Tanzania, focused on improving foundational numeracy through an AI-driven assessment program, with eBASE Africa leading the evaluation. It was a huge learning curve, but also a chance to step up and contribute meaningfully. Getting up to speed required intentional effort. I immersed myself in understanding project goals, the theory of change, evaluation framework, tools, indicators, and datasets. I spent long hours reading through documentation, asking clarifying questions and reviewing past reports. While there were moments of uncertainty, I also found moments of clarity and deep insight that strengthened my confidence. I took every opportunity to learn and grow. One of my key responsibilities was refining our data collection tools. This went beyond form design, it required appreciating the nuances of education systems in Ghana and Tanzania, adapting tools to local contexts, and ensuring methodological rigor. I worked to align pre- and post-test tools with project outcomes and to ensure that indicators reflected meaningful learning changes. This experience taught me that evaluation isn’t about ticking boxes, it’s about asking the right questions and capturing insights that matter. Pictured, Charlotte with the Lead For Ghana Team and some Teachers on the field during Endline Data Collection Cross-country collaboration brought its own lessons. Coordinating between partners in Ghana and Tanzania, navigating different schedules, time zones, and education calendars required patience, strategy, and above all, clarity. I learned to communicate with precision. I learned how to schedule follow-ups without sounding pushy, how to facilitate meetings where every voice was heard, and how to respond when data didn’t come in as planned. There were moments of true frustration, when a partner misunderstood a tool, when data came in with missing values, when we had to revise timelines because of unforeseen field constraints. But I also started to see the big picture. I began to grasp how all these moving parts fit together. With each problem, I discovered new ways of thinking. I started anticipating issues before they happened. I created tracking templates, revised fieldwork guidance notes, and led internal review sessions with partners. I was becoming someone the team could rely on, not just to execute tasks, but to lead and adapt. One moment that stands out vividly is my visit to one of the pilot schools while in Ghana. I observed a teacher use the AI-powered feedback tool to adapt his lesson, based on learner performance. The precision with which he identified learning gaps was incredible. And what moved me most was his excitement when he realized it was effective. He said, “Now I can understand what my learners need, even before they speak it.” That moment stayed with me. It validated everything, the stress, the revisions, the back-and-forth. It reminded me that our work wasn’t theoretical. It had a real impact. This experience didn’t just enhance my technical skills, it reshaped the way I see myself and my role as a young evaluator. I developed a stronger analytical mindset. I now approach problems with more confidence, breaking them down into components and systematically thinking through solutions. My writing improved significantly. I learned how to frame findings for different audiences, donors, educators, community members, and how to strike the balance between technical depth and accessibility. I became more grounded in participatory approaches. I actively sought feedback from partners, reviewed translation protocols to ensure questions made sense in local languages,(case of Tanzania) and began to view data as a conversation rather than a transaction. I realized that evaluation is not about being the expert who arrives with answers, but about being the listener who asks the right questions. And yes, I made mistakes. There were tools I revised too many times. Reports that had to be redrafted. Graphs that didn’t quite tell the story. But each mistake was a lesson, and I was fortunate to have a team that encouraged growth, not perfection. Every challenge became an opportunity to refine my skills. By the end of the project, I could confidently design MERL frameworks, develop outcome and process indicators, and manage complex stakeholder dynamics. I have gone from a young woman unsure of her place in the project, to a young evaluator who can lead with purpose and clarity. As such, the DAARA Innovation Fund didn’t just fund an evaluation, it funded my transformation. It created space for a young African woman to step into leadership, to learn through doing, and to build competence through trial and reflection. It allowed me to sit in meetings I once felt unqualified for, and leave those meetings with clarity, action points, and, sometimes, even answers. A heartfelt thank you to my collaborators, Charles from Shule Direct, and Grace and Peter from Lead for Ghana, for making cross-country collaboration feel seamless, even when the road was anything but so. Yes, there were challenges and hiccups, but your professionalism made all the difference. To my colleagues working on other Daara Innovation Fund projects at eBASE, thank you for having my back. As the new girl navigating unfamiliar territory, your […]

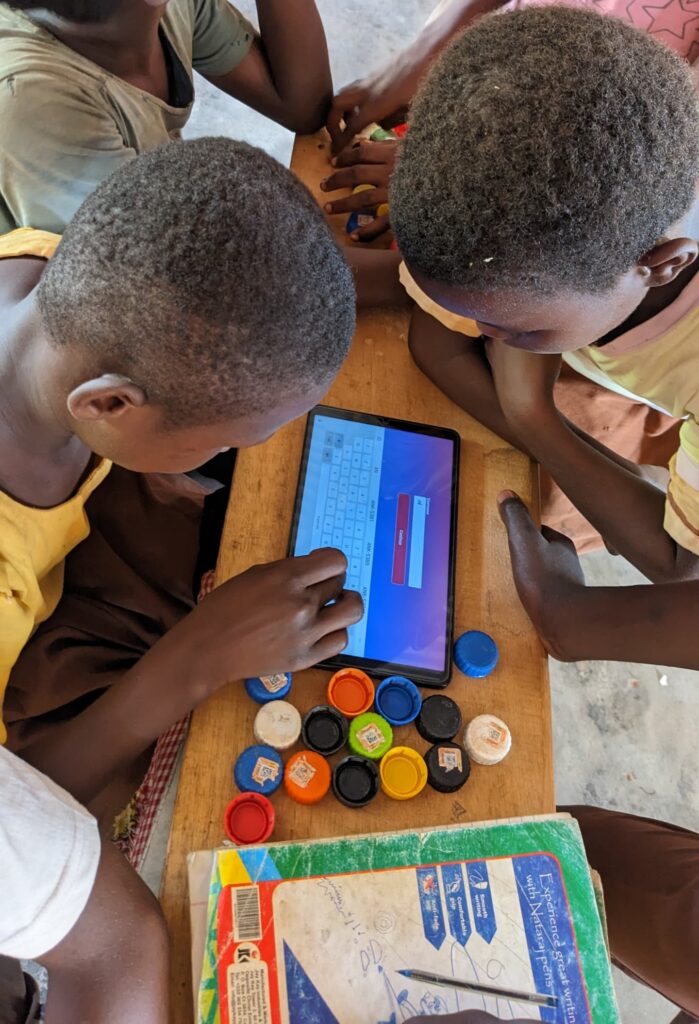

Introduction Launched in 2024, the Daara Development Academy is a co-created initiative designed to strengthen the capacity of African organizations to scale evidence-based solutions for foundational learning. An important component of this program was an Innovation Fund, intended to support collaborative projects between Daara partners that address sector needs to improve foundational learning outcomes. Projects could include the development of approaches, tools, and resources that align good practice within the Cohort with the science of teaching principles. The AI Teachers project was awarded funding through this Fund and was piloted in Ghana and Tanzania to explore how AI-powered digital platforms can enhance teacher competencies and improve student learning outcomes in numeracy. The initiative aimed to provide teachers with real-time data on their students’ learning and differentiated instructional support aligned to national curricula. Implementation was led by consortium lead Shule Direct in Tanzania, with implementation support by Lead for Ghana in Ghana. eBASE Africa ensured the monitoring and evaluation of the project across both countries. Overview of the project Foundational learning in Africa faces a severe crisis, with alarming data indicating that at most one in five children acquire basic reading and mathematics skills by the end of primary school. Government data from Ghana and Tanzania echoes this, revealing that only 31% of Tanzanian Class 3 students can solve Class 2 multiplication problems, and less than 40% of Ghanaian primary students achieve math proficiency, hindering their academic journey. This crisis is fuelled by large classes, a lack of qualified teachers, outdated teaching methods, and limited access to up-to-date resources, especially in rural and underserved areas. Recognizing AI’s potential to address many of these challenges through individualized learning, teacher support, assessment-informed instruction, and accessibility, the consortium developed and piloted an AI-powered, data-driven platform. This platform supported teachers by providing real-time student assessments, resources to enhance their instruction, and AI-generated insights. The “AI Teachers: improving teachers’ competencies through an AI-driven assessment program” initiative aims to empower teachers with differentiated instruction and assessment tools, ultimately improving numeracy skills for learners in Ghana and Tanzania. Through structured workshops, coaching, and feedback sessions, the AI-powered platform provided essential support to teachers, boosting student engagement and performance. Brief overview of the evaluation approach The evaluation of this pilot project employed a mixed-methods design to assess the executability of the intervention, improvements in teacher capacity, uptake and maintenance of evidence-based practices, and early indicators of student learning as a proof of concept. The pilot study was conducted across 14 schools in Ghana and Tanzania, involving a total of 36 teachers and 400 learners. In Ghana, the study focused on Grade 3 classrooms in nine schools across three regions, engaging 16 teachers and 185 learners. In Tanzania, the study targeted Grade 1 and 2 classrooms in five schools, involving 20 teachers and 215 learners. The selection process in both countries aimed to ensure a diverse representation of educational settings, with a shared emphasis on classrooms where foundational numeracy skills are most critical. Quantitative tools included EGMA-aligned learner assessments, JBI audit checklists, and TAM-informed teacher surveys. Qualitative insights were gathered via key informant interviews, classroom observations, and reflective logs. Endline data were compared with baseline to assess changes in teaching behaviour, AI adoption, and student numeracy performance. The program garnered significant endorsement from the government, evidenced in Tanzania by the active involvement of regional and national education officers who subsequently requested teacher capacity building and invited the program to inform the National education teaching strategy. Overview of the findings Project Executability In Ghana, 93% of teachers were using the platform daily by the endline, up from 75% who initially planned to use it daily. In Tanzania, teacher usage of AI tools increased from 30% at baseline to 85% at endline, showing strong uptake despite infrastructure challenges such as limited devices and intermittent internet access. Teachers described the platform as user-friendly and motivating: “The more I used the App, the easier it became to plan and deliver my lessons,” said a Ghanaian teacher. In Ghana, teacher compliance with best practices improved from 80% at baseline to 88% at endline. In Tanzania, compliance rose from 85% to 90%. Teachers grew more confident in using AI, with 71% of Ghanaian teachers reporting they felt “very comfortable” using the platform by endline, up from 44% at baseline. A Tanzanian teacher said, “I now check student performance daily and ask myself whether the teaching methods I used were effective”. These quotes reflect a shift in teacher behaviour toward more data-informed and responsive instruction. Learning outcomes improved in both countries. In Ghana, average learner scores increased from 62% at baseline to 76% at endline. The proportion of students in the “Poor” performance category halved from 22% to 11%, while those rated “Excellent” rose from 34% to 43%. In Tanzania, the number of learners in the “Poor” and “Below Average” categories dropped to zero, while the proportion rated “Good” more than doubled from 7% to 15%, and “Excellent” rose from 82% to 85%. “Students who previously struggled to recognize numbers can now confidently identify and differentiate them,” said a Tanzanian teacher. Both studies faced notable limitations that must be considered when scaling. Infrastructure challenges, such as poor internet and limited devices constrained the implementation. Teachers’ unfamiliarity with AI, delays in app deployment, and fixed, non-adaptive content design also limited personalized learning and reduced the accuracy of learner performance data. Case for follow-up and scale This project successfully developed and tested a minimum viable product (the AI-powered platform), demonstrating strong feasibility, high acceptability among teachers, and clear shifts in instructional behaviour across diverse classroom contexts. The positive results signal a unique opportunity to invest in the development of a more complete, contextually relevant AI tool, tailored to the realities of Africa’s low-resource settings. Read the full report Here

Introduction Launched in 2024, the Daara Development Academy is a co-created initiative designed to strengthen the capacity of African organizations to scale evidence-based solutions for foundational learning. An important component of this program was an Innovation Fund, intended to support collaborative projects between Daara partners that addresses sector needs to improve foundational learning outcomes. Projects could include the development of approaches, tools, and resources that align good practice within the Cohort with the science of teaching principles. The project “Using assessment for learning to enhance numeracy instruction” was awarded funding through this Fund and brought together four African organizations: The consortium was led by TEP Centre which also led the implementation in Nigeria, while Funda Wande led implementation efforts in South Africa and Zizi Afrique, implementation activities in Kenya. eBASE Africa was responsible for evaluation and evidence generation. Case for follow-up and scale The teacher-centered numeracy intervention rooted in error analysis and formative assessment has suggested strong feasibility, clear instructional value, and early signs of impact across three diverse education systems in Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya. Teachers not only adopted new practices but sustained them. Learner outcomes improved significantly, classrooms became safer, more reflective spaces where learners actively discussed their mistakes, and teachers treated errors as opportunities for learning. With a scalable, low-cost model and a strong foundation of cross-country collaboration, the consortium are poised to expand this approach to reach more schools and teachers across Sub-Saharan Africa and design a rigorous impact evaluation of the program to generate robust evidence needed to embed this practice into national instructional reform. Overview of the project This project addresses two critical challenges undermining foundational numeracy in Sub-Saharan Africa: low learner performance in early-grade mathematics and the difficulty teachers face in sustaining improved instructional practices without ongoing support. Evidence from Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya highlights that, despite training, many teachers struggle to implement effective teaching strategies, and learners continue to face persistent difficulties with key numeracy concepts such as place value and two-digit operations. The proposed solution was to equip teachers with practical tools and structured support to use error analysis as a formative assessment technique. By identifying and interpreting learner errors, teachers can adapt their instruction to address specific misconceptions, transforming mistakes into valuable learning opportunities. The project developed mobile-friendly, evidence-based guides and facilitated collaborative lesson planning tailored to national curricula. Implemented in phases across Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa, the initiative aimed at building teachers’ capacity, promoting sustained pedagogical change, and ultimately improving numeracy outcomes for early-grade learners in under-resourced settings Brief overview of the evaluation approach The evaluation of this proof-of-concept project employed a mixed-methods design to assess the feasibility of the intervention, improvements in teacher capacity, the uptake and maintenance of evidence-based practices, and early signs of student learning. Data collection was conducted at three time points in Nigeria and South Africa, and at baseline and endline in Kenya, focusing on teacher practices, learner engagement, and student performance. Quantitative data were collected through standardized learner assessments, teacher audits, and structured classroom observations, while qualitative insights were obtained from key informant interviews and teacher diaries. Instructional shifts and learner engagement were tracked using audit checklists and observation rubrics, and weekly error logs helped identify common misconceptions to inform lesson planning. The evaluation was further supported by coaching sessions based on audit findings and regular WhatsApp check-ins, offering real-time feedback and support. This triangulated approach provided a robust assessment of the intervention’s feasibility, impact, and emerging evidence of promise in resource-constrained classrooms. Overview of the findings Initial results from Nigeria and South Africa, with partial data from Kenya, show clear progress across four key outcomes. First, teacher capacity in error analysis and formative assessment improved significantly. In Nigeria, teachers advanced from basic error detection to diagnosing misconceptions and adjusting instruction. In South Africa, 50% of teachers at endline defined error analysis as identifying, analysing, and understanding learner errors. In Kenya, among the 19 directly trained teachers, 93% corrected learner errors, 86% identified misconceptions, and 100% offered targeted feedback, though 33% struggled to consistently update error logs due to workload. Teachers increasingly moved learners from basic counting strategies to place value methods. Second, teacher attitudes and behavior improved. In Nigeria, compliance with best practices rose from 36% to 79%; in South Africa, from 16% to 74%, with 71% of teachers reporting greater confidence in using error analysis. In Kenya, 87% facilitated error discussions, 93% adjusted lesson plans based on insights. Third, student engagement increased. In Nigeria, engagement rose from 49% to 72%, with 75% of teachers observing learners explaining their thinking and 70% reporting peer correction. In South Africa, engagement improved from 56% to 64%, and 62% of teachers reported learners were more willing to explain their reasoning. In Kenya, 50% of learners were discussing mistakes at baseline, 100% felt safe doing so, and peer correction was observed in 50% of lessons at endline. Finally, there are promising indications that learner performance in foundational numeracy improved. In Nigeria and South Africa, factual and conceptual errors in addition declined, though procedural errors remained, with 78% of procedural errors in Nigeria tied to subtraction with regrouping. In Kenya, where over 80% of errors were factual at baseline, scores rose from 19% to 43%, including 27% to 46% in addition and 12% to 39% in subtraction. These findings suggest that targeted teacher training in error analysis could potentially lead to more responsive teaching and better learning outcomes, while also highlighting the need for continued support to deepen understanding and sustain progress. Another notable outcome of the project is the establishment of key collaborations that built pathways for sustainability, notably in Kenya where the project was done in close partnership with the government, providing them with critical insights into learner numeracy challenges that are now being addressed through new approaches to teacher professional development. Read the full report Here

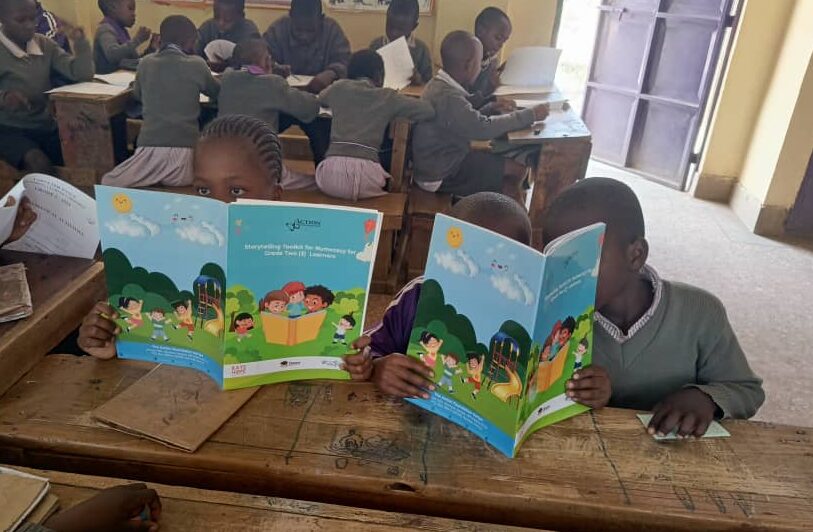

Introduction Launched in 2024, the Daara Development Academy is a co-created initiative designed to strengthen the capacity of African organizations to scale evidence-based solutions for foundational learning. An important component of this program was an Innovation Fund, intended to support collaborative projects between Daara partners that addresses sector needs to improve foundational learning outcomes. Projects could include the development of approaches, tools, and resources that align good practice within the Cohort with the science of teaching principles. The project “Play-based learning: integrating narrative-based mathematics to improve numeracy outcomes” was awarded funding through this Fund and brought together three experienced African organizations: The consortium was led by The Action Foundation, which also led implementation efforts in Kenya. Rays of Hope led implementation activities in Malawi, while eBASE Africa was responsible for evaluation and evidence generation. Case for follow-up and scale Our innovative, low-cost, inclusive narrative-based numeracy approach has proven highly feasible, deeply acceptable to educators, and shown compelling early promise to improve numeracy learning in Kenya and Malawi. Education leaders in both nations are enthusiastic and eager to integrate it into national curricula, presenting a significant opportunity for transformative change. To build on this momentum and rigorously validate its impact on numeracy outcomes, a follow-up phase would solidify these gains and generate robust evidence for national numeracy strategies. Scaling this promising model involves expanding to more schools and students while embedding rigorous evaluation methodologies to definitively demonstrate impact and measure effect sizes. Overview of the project Foundational learning outcomes, especially in mathematics, in Kenya and Malawi present a significant challenge. Government data in Kenya indicates that less than half of Grade 2 and 3 learners achieve numeracy proficiency, particularly among children in informal settlements and those with disabilities. Traditional, lecture-based instructional methods have proven insufficient in fostering conceptual understanding or building learner confidence and engagement in mathematics. To address this, the consortium piloted narrative-based mathematics, utilizing storytelling as a pedagogical tool to transform math instruction. Teachers received training to integrate short, culturally relevant stories into lessons covering core numeracy concepts such as patterns, number sense, geometry, and arithmetic. Through structured workshops, coaching, and feedback sessions, storytelling served as a crucial scaffold, enhancing student engagement, mathematical reasoning, and critical thinking in the classroom. Brief overview of the evaluation approach The study employed a mixed-methods design to assess the executability of the intervention, improvements in teacher capacity, uptake and maintenance of evidence-based practices, and early indicators of student learning as a proof of concept. Conducted across 10 schools—8 intervention and 2 control—in Kenya and Malawi, the study involved 300 Grade 2 learners and 15 teachers. As part of a piloted experimental approach, one control school in each country served as a comparison arm to assess differences attributable to the intervention. The evaluation triangulated data from standardized learner assessments (EGMA in Malawi and WINGS in Kenya), a 29-item classroom audit checklist to track teacher compliance with evidence-based practices, and structured learner engagement surveys. Complementary qualitative data were gathered through key informant interviews, classroom observations, and focus group discussions with teachers to explore fidelity, contextual relevance, and instructional shifts. The intervention ran for four months in Kenya and six months in Malawi. Teachers participated in initial training and received ongoing support through structured feedback sessions—one in Kenya and two in Malawi—facilitating adaptive learning and implementation refinement. Overview of the findings The intervention demonstrated strong project executability across both contexts, with all intervention schools successfully delivering the storytelling-based numeracy lessons within the allocated timelines. Teacher participation was high, and implementation fidelity improved with structured feedback cycles, demonstrating acceptability of the intervention. The intervention was equally well received by decision makers. The Chief Education Officer for Blantyre, Malawi, reinforced this sentiment, stating, “I strongly believe this initiative should be expanded to all schools in the region because teachers truly need this kind of support. There was a clear improvement in teacher capacity, particularly in instructional planning, formative assessment and direct explicit instruction. In Malawi, teacher compliance with evidence-based practices rose from 50% at baseline to 92% at endline; in Kenya, it increased from 69% to 85%. Teachers reported greater confidence in delivering content and adapting stories to learner needs. These improvements translated into sustained behaviour change, even in the absence of external support. Teachers consistently applied key elements of the intervention—storytelling, formative assessment, and learner-centered questioning—after initial training. In Malawi, teachers exposed to two rounds of feedback maintained higher levels of compliance, suggesting that even short-term coaching can anchor behavior change. One teacher in Malawi remarked, “I feel more creative when I create my own stories… I will continue using stories even after the project ends, I love the approach”. In Kenya, a teacher noted, “I used to struggle to teach patterns, but with the stories, it’s very easy”. Learner engagement significantly increased, especially in Malawi where consistent participation rose from 25% to 82%. In Kenya, the increase was from 26% to 65%—while control groups remained below 37% in both contexts. Teachers equally highlighted increased motivation: “My learners are very excited about stories… even my slow learners are interested”, and “[s]tories have increased attendance; learners want to come and listen”. Learner performance also improved. In Kenya, learners below expectations in pattern recognition fell from 47% to 8%, while in Malawi, the percentage of learners struggling with number discrimination dropped from 37% to 0%. Gains in addition skills in Malawi were especially strong, with a 49-point improvement. These changes were not observed in control schools. Read the full report Here

Daara Development Academy for Sub-Saharan African implementers of foundational learning We are facing a global learning crisis whereby millions of children are in school but are not learning at satisfactory levels. Learning outcomes within Sub-Saharan Africa are particularly dire, with 9/10 children not able to read with comprehension by 10 years of age (compared to 9/10 children in high-income countries). To improve the quality of education, a rigorous focus on teaching and learning is needed, combined with local contextual solutions, led by local implementers. The Daara Development Academy (Daara) aims to strengthen the capacity of local implementers within Sub-Saharan Africa, to champion and enhance their efforts in advancing learning outcomes at scale. The Program has been co-created by 11 organizations across Sub-Saharan Africa, coordinated by Better Purpose, and funded by the Gates Foundation. The Program has five primary learning goals which focus on the biggest barriers to each organization in achieving its strategic aims: Building pedagogical excellence – strengthening organizations’ understanding of the science of teaching and learning, how to effectively translate this into classroom practice and programming. Using and generating evidence – solidifying organizations’ approaches to leveraging data ensuring programming and impact is evidence-driven. Moving successfully to scale – supporting organizations to design programs for scale, to work effectively with government. Managing talent to build the organization – reinforcing organizations’ talent management strategies ensuring fit for organization and market. Strengthening fundraising capability – supporting organizations to enrich their understanding and engagement with the funder landscape. Learning will happen through study tours, expert lectures, workshops, conferences, coaching, consultancy support and technical assistance, with a focus on collaboration and peer learning amongst the cohort. The Program will also comprise of an Innovation Fund. This is a central fund designed for Daara Partners to propose and bid for collaborative projects seeking to improve FLN outcomes. Ultimately, Daara aims to better equip local Sub-Saharan African organizations to that they can lead the transformation of education for children in Africa, resulting in drastically improved learning outcomes. If the first cohort shows signs of success, it could continue for future cohorts, and we will be seeking a Sub-Saharan Africa based grant manager to take over the role from Better Purpose. If you would like to know more about Daara, its organizations or how you can support the Program, please get in touch with simi.otusanya@betterpurpose.co or rigobert.pambe@betterpurpose.co